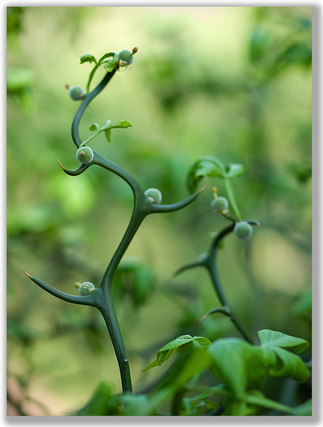

Single Tear Single Tear Chris Fedderson — MacroFine Musings [This post is an elaboration on the first point I made in my post of November 10, 2015, Five ways to raise your photo IQ (Interest Quotient)] ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ But focus you must! OK, so you have a visualization, including the hook. Your subject is pristine — no one wants a technically perfect picture of a raggedy butterfly. You have the lighting and composition perfect. Your color is balanced — chromatically and ‘geographically’ within the image. So shoot the image already, right? NO! You need to focus. Well, duh. But, it is more complicated than just that. You can’t just set your aperture at f/22 and use auto-focus and hope everything works out. More likely than not you don't want everything in focus. You might want just your hook in focus and the rest to be only ‘suggestions’ of imagery or background or backstory or supporting elements. In image #1 below, I saw a single twig that I wanted to feature. Clearly, at f/22, too much is in focus to allow the one twig to be accentuated; it gets lost in the jumble. However, as shown in #2, an aperture of f/2.0 blurs out all the extraneous distractions so we can now clearly see what The Point Is. You achieve this selected focus by employing your aperture control to regulate your depth of field. I’m not going to ‘go all techy on this’, but suffice to know:

Experiment. Using a tripod, beanbag, or some other means to be hands-free with your camera and with your smallest f/number (maybe f/2.0), manual focus on an object at a short distance away. Snap the shot. You might have (just pulling examples out of my hat) things between 4.0 to 4.5 feet away in focus and everything else, closer and farther away, in graduated out-of-focus-ness. Now don’t touch anything! Change only your f/number to your largest (maybe f/22). Snap the shot. Now you might have everything from 2 feet to 20 feet in focus and things closer than 2 feet and farther than 20 feet in graduated out-of-focus-ness. Now — again, without changing anything but the aperture — do all the (major) f/stops, i.e., 2.0, 2.8, 4.0, 5.6, 8.0, 11, 16, 22 and see the depth of field gradually change. Now do it again focusing at maybe 15 feet away. Now memorize all these results. Memorize all these results?! Are you crazy?! No! Yes! No! I mean, don’t memorize them, just pay attention to the general results. With time, attention, and hundreds of experimental shots, you’ll start to get a ‘feeling’ for which settings are close to what will give your hook the attention it deserves. Then you just shoot a variety of shots so —maybe— one will be your intended image. In doing this, you will continue to hone and refine your skill, and ultimately you’ll need to shoot fewer ‘maybes’. So you did all this and your hook is still not focused correctly. There are a several reasons this might be happening.

I can’t help you with motion blur, except to say possibly a faster shutter will solve the problem — but then you change up your aperture and hence the depth of field and maybe there goes your hook and you get all distraught and you never come out of the house again and you quit using personal hygiene and all your friends and spouse abandon you… Whoa, hold on there, Chief, it’s not that bad. Just move on to your next hook. There are literally (and I do mean literally!) infinity times infinity hooks out there. Go get one! Now, camera shake I can do something about! Phfwew! See, that wasn’t so bad. The solution? Stop hand-holding your camera. Simple as that. Get a tripod. Don’t have, or unable to get, a tripod? Try using a beanbag and set your camera on top of a rock or fence post or your car hood or the ground or any other thing in the universe that is not moving. Don’t have a bean bag? Make one out of one of your socks and small pebbles. OK, that was dumb. But make one out of an old sock and some dried beans. Or use your camera bag or purse to prop your camera on — be sure it is secure and won’t tilt off and fall. Bummer. Add in the use of your in-camera shutter release timer or a cable shutter release and you are all set to be jiggle-free. The issue with auto focus is the easiest to remedy… just use manual focus. I will use auto focus to find my point and to get a rough… let me repeat… rough focus, and then I’ll manually tune it in from there. Even if auto focus seems to have worked perfectly, it will refocus again with each shutter release and there-in lies great potential for miss-focusing.

Remember that you are not focusing on a thing but rather you are focusing on a distance from your camera. Any subject that comes into, or goes out of, that distance will come into, or go out of, focus. And, any thing that changes the relationship of your hook to that distance will alter the ‘total-focal-effect’* (I just made that up!) within your image. You may still have razor sharp focus — just on the wrong element in your image — or you may have generalized blur from movement of the subject or the camera. Sometimes whatever went wrong can be corrected, sometimes not. Experiment to learn what you can control, and when you cannot, move on to your next stunning image. Thank You for visiting, — Chris P.s. * Total-focal-effect: all the aesthetics, impressions, feelings, emotions, points-of-attention, appreciation, etc., derived, en masse, from the collective effects of in-focus and out-of-focus areas and elements within an image. So what do you think? Is this focus-thing clear to you? Do you have a sharp understanding of it? Or is it still a little blurry? Do you want more depth? Or would you rather stay soft on the matter? If I’ve not been well-defined on something please do send a comment and I’ll see if I can bring it into focus!

0 Comments

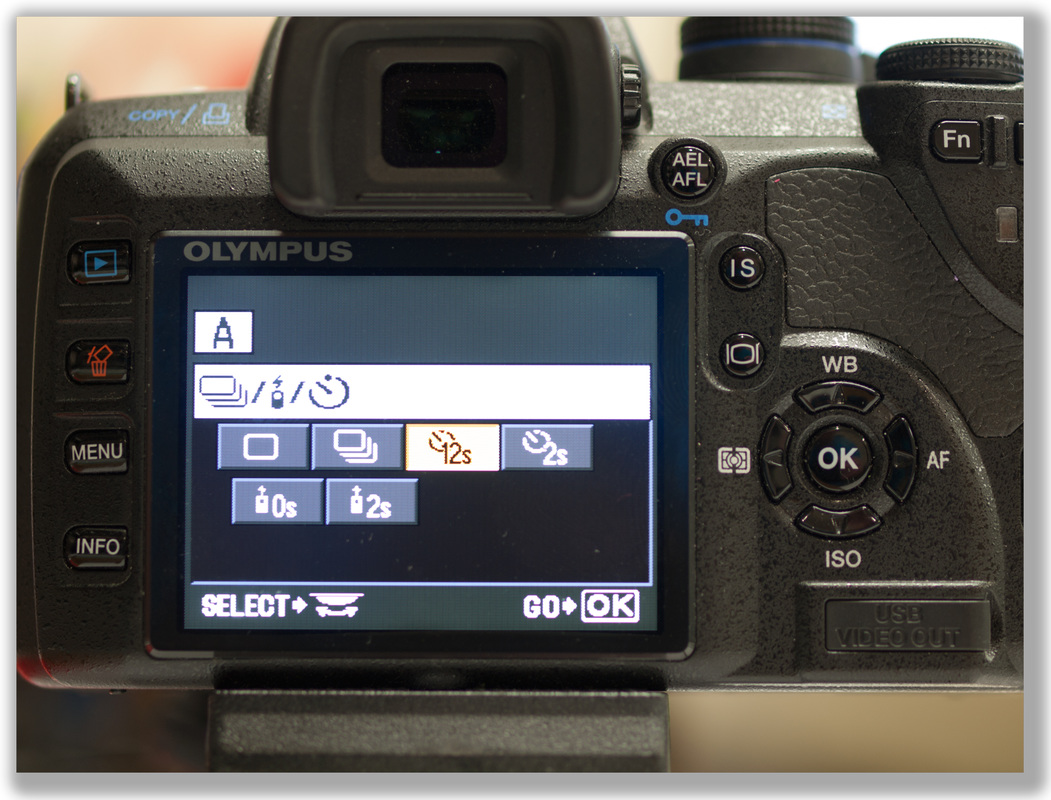

Chris Fedderson — MacroFine Musings ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Art fairs really do get people thinking. Here you are, visiting an Art Fair, chances are you think you’re not particularly artsy-fartsy yourself (but you probably are, in some way or another — but that’s another post for another time), and you’re looking at things you’ve never seen before, let alone that you would conceive you could make. Soon you start asking, “how’d you do that?”, “where do you get your ideas?”, “what’s this made of?”, “what kind of tool did you use for that effect?”, and on and on. And so it is in my booth, too. Artists generally do enjoy talking about their work — it’s another way to share, after all. I know I enjoy it, especially when I get to talk with a young Artist-In-Training. I visualize them on a meandering path through the Career Fair, gaping at all the possibilities. Much like this Ladybug on its Pilgrimage.  Green Spring Gardens, Virginia Green Spring Gardens, Virginia What I find interesting is that of all the questions I get asked, three rise to the top to be the three most frequently asked, and this holds true whether I’m talking with a student photographer or someone who has been shooting for years and possibly has their own photography business… 1. Where do you take your images? I take most of my images at botanic gardens, arboretums, and parks. Since I’m shooting close-ups of flowers, bugs, small animals, natural textures and patterns, and the like, I find an abundance of subject matter in these places. But the point here is you need to go to where your subjects are. Yes, this goes without saying. But what if you don’t know what your subject is to be? Meaning… what if you haven’t decided on what type of photography (or any art, for that matter) you want to concentrate on? Then you’re in a good position to justify doing all kinds of things and trying all kinds of variations and even changing up entirely and doing something completely different until you find your calling! Throughout all of my photo’ing life I have always gravitated toward shooting the small, seemingly unspectacular elements in nature; hence my work in close-up and macro photography. But I have also tried shooting street candids, ‘portraiture’ at family gatherings, architecture, and many other types of spontaneous snaps. But none of those artistic styles struck a chord with me. So I ‘found’ myself — and find myself — in botanic gardens, or my own backyard, where my mind’s eye goes wild! 2. What type of camera do you use? Ansel Adams said. “The single most important component of a camera is the twelve inches behind it.” I have to agree. My complete equipment list includes: an Olympus E-30 DSLR, a 50mm macro lens, a 50-200mm telephoto zoom, and occasionally a polarizing filter or a reflector or diffuser. That’s it. But this equipment is all driven by the same computer — my brain, as it is directed by my Mind’s Eye. You see, it is not the equipment that makes the photographer; it is the photographer’s vision and visualizations. I would take the same images I am now even if I had $1,000,000 worth of hardware. No better. No worse. I think the secret answer to the equipment dilemma is this: ** Learn your existing camera and lens(es) — go through the user's manual over and over to learn all the tools, bells, and whistles and what they can do for you. ** Figure out what they can do and what they can’t — don’t expect it to be a 500mm telephoto and a 10x macro simultaneously… unless it is! ** Determine whether they are capable of producing the images that you’re visualizing — assess how well, or even whether, your equipment is suited to your photographic vision. If you don’t yet have a camera and lens suited to your goals, but have researched and know generally what parameters this new equipment needs to satisfy, then employ what I just decided to call the Minimum/Maximum Rule. Buy only the minimum amount of equipment that you'll need. Now go Maximum… figure out what the absolute maximum is that you can afford to spend, and boost that by a ‘little bit’ more. This will get you the best quality possible of the essential tools you need, without your ending up with a lot of pieces of questionable-quality equipment you really didn’t have any need for in the first place. 3. How do you get your colors to be so vivid? Lastly… my colors. What I answer here can apply equally to Black and White images because it is less about the actual color than it is about, oh, everything else. It begins in the ol’ Mind’s Eye. After I’ve found a great hook containing a stunningly poignant visual and a heart-wrenching emotion, I look for more than just the presence of color. I want great color contrast, color juxtaposition, color coordination, color depth — or softness, color framing elements within the image, color balance… (or all these same things in B+W). Then it’s to the darkroom. By that I mean I’ve got my computer and printer set up in a dark… room. ;-) About 12-15 years of Photoshop experience now comes into play to do adjustments to the images such that the printer will print them to appear as close to real life as is possible. I use an Epson 3880 wide format professional printer using a system of nine, highly-pigmented inks together with art papers and print resolutions as high as 2880 dpi. Finish it all with black mats to make the images “pop” in your mind’s eye. That’s ‘all’ there is to it. Easy Peasy. When you find yourself a few years shy on your Photoshop experience or a couple inks short in your printer… do not despair. There are a billion contract printers available who would love to help you realize your vision. I have always done my own printing so I regret that I don’t have any direct referrals, but I can suggest some selection parameters:

Now get out there and let’s get shooting! Thank You for visiting, — Chris P.s. What is your top question? Or your biggest dilemma? Do you print your images or do you have them printed at a print shop? How is that working? Have you found any pitfalls that others should avoid? Please leave your thoughts in the comments and we can start a conversation. Thank You. |

Categories

All

About Chris

I am a Virginia-based photographer and gather my images while hiking in parks and natural areas here at home and in the locations I travel to. I also love to visit arboretums and botanic gardens to find unusual and exotic subjects. Archives

March 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed