|

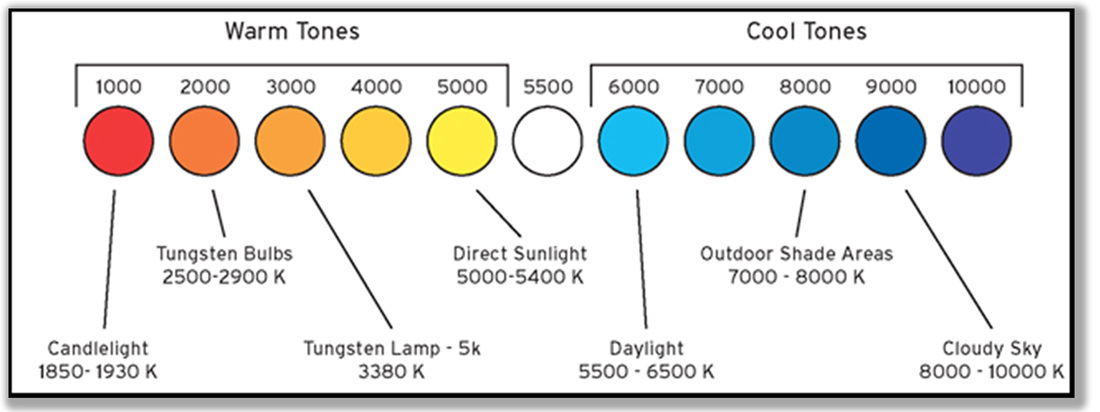

Chris Fedderson — MacroFine Musings [This post is an elaboration on the third point I made in my post of November 10, 2015, Five ways to raise your photo IQ (Interest Quotient)] ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ But not just any light . . . Is it sunlight? Fluorescent light? Candle light? Side light? Back light? Bright light? Diffused light? Colored light? Mottled light? Half-shadowed light? It gets worse… what temperature is the light? I don’t mean is it a hot day or a freezing day, but rather, what is the Kelvin Color Temperature? From Wikipedia: The color temperature of a light source is the temperature of an ideal black-body radiator that radiates light of comparable hue to that of the light source. What does that mean?! Yeah, I don’t know either. At least not in all its Technicolor Glory. In general terms, though, the Color Temperature that White Balance refers to is where a particular light falls on a scale from warm to cool, and covering this fully would be a book in itself. Your camera manual will likely have a chart showing this relationship — at least with regard to how it meshes with your camera’s setting choices. I’ve shown a simple chart here, but if you really want to read in-depth, you might start with Wikipedia or these guys or maybe these other guys. Since I do most of my shooting outside in daylight, and since daylight white balance is probably the easiest color temperature for the camera to determine, I often delegate this chore to the camera’s computer. I use Auto-WB a vast majority of the time. But, I do look at the different WB settings available to see what differences it might make. These shots show the camera overlaying the menu control on the monitor image to give you an indication of what the specific WB setting will produce. It is only an indication, though, so experiment to see how this might enhance your imagery.

You can also set a custom WB. Probably most applicable to strict studio work where you don’t have pure daylight but maybe a mix of daylight from a window (a very, variable light source) mixed with artificial light from incandescent or fluorescent lights of who-knows-what temperature, and possibly your flash added in. You’ll find the instructions to do this in your camera manual. So after all that, you decided to just use Auto White Balance? OK, but you’re not out of the woods, yet! There are still potential issues related to an over abundance of — or lack of — light on and around your subject, i.e., the quantity of light.

These problems can all be addressed by one, or both, of two solutions. You need to either add light or you need to reduce light at a given spot. I’m not going to cover flash here — that, too, could be a book in itself — but rather some techniques for rearranging the available light; for bringing light to a subject and for reducing the light falling on your subject. Of course you can buy all sorts of reflectors, shades, umbrellas, diffusers, and don’t even start talking about light sources! But you can also do a very serviceable job with little-to-no expense.

When you want to expand on these light-altering techniques, there are more things you can try: metering tricks, exposure compensation, and of course, flash and other external light sources. So try everything you can think of, and have fun experimenting! This image, Lily Grace, shows use of metering to achieve unique lighting. I’ll cover use of metering in a future post . . . So Don’t Touch That Dial!

Thank You for visiting, — Chris P.s. What really Outside-the-Box things did you try? What worked? What didn’t? What gave you great — unexpected — results? What are you going to try next?

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

About Chris

I am a Virginia-based photographer and gather my images while hiking in parks and natural areas here at home and in the locations I travel to. I also love to visit arboretums and botanic gardens to find unusual and exotic subjects. Archives

March 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed